[Disclaimer] This article is reconstructed based on information from external sources. Please verify the original source before referring to this content.

News Summary

The following content was published online. A translated summary is presented below. See the source for details.

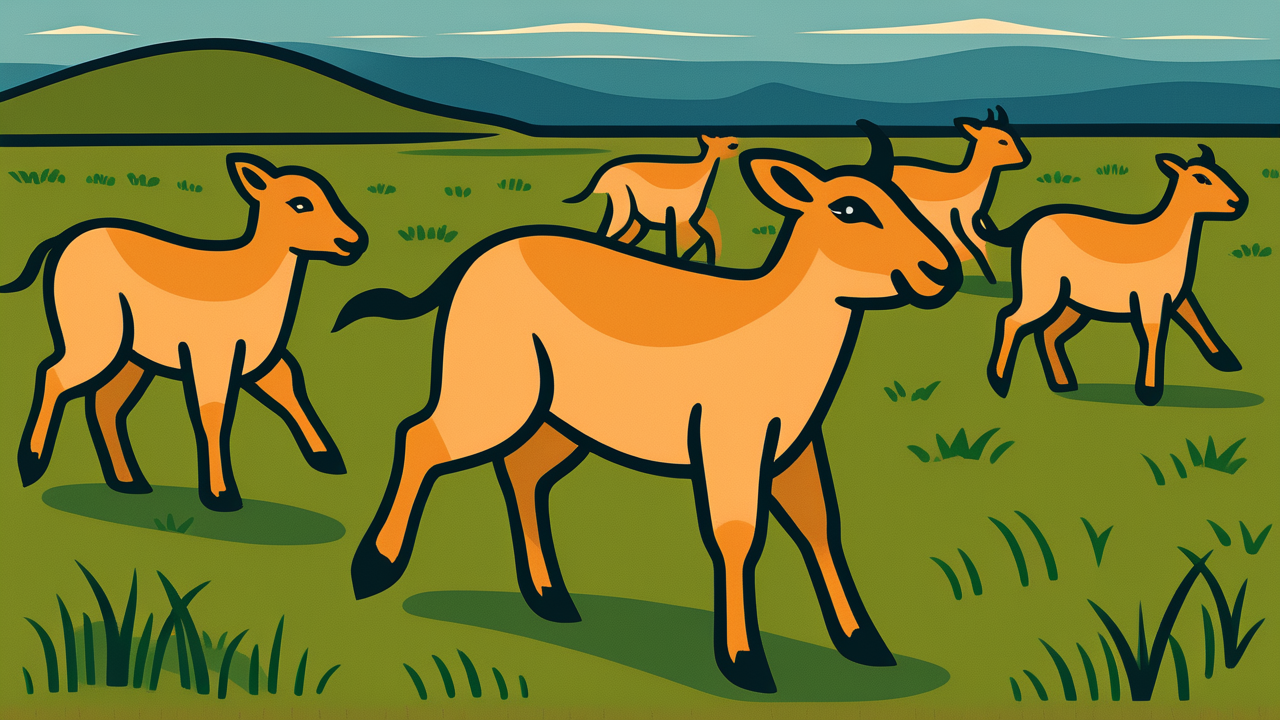

Kazakhstan’s saiga antelope population has made a remarkable recovery from near extinction, growing from just 50,000 animals in 2005 to over 2 million today. This prehistoric-looking antelope with its distinctive inflated nose structure once roamed across Central Asia in vast herds. However, after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, widespread poaching for their horns (valued in traditional Chinese medicine) and habitat loss nearly wiped them out. A catastrophic disease outbreak in 2015 killed over 200,000 saigas in just three weeks. But through strict conservation efforts, anti-poaching patrols, and protected areas, the population has rebounded so successfully that farmers now complain about crop damage. The government is exploring sustainable management strategies, including limited hunting permits, to balance conservation success with local community needs.

Source: Global Voices

Our Commentary

Background and Context

The saiga antelope is one of Earth’s most ancient mammals, having survived since the Ice Age alongside woolly mammoths and saber-toothed cats. These unique animals are perfectly adapted to Kazakhstan’s harsh steppes, with their inflatable nose structure filtering dust in summer and warming freezing air in winter. Saigas can run up to 80 kilometers per hour and migrate hundreds of miles searching for fresh grass.

During Soviet times, saiga populations were carefully managed and numbered in the millions. The government regulated hunting and protected migration routes. However, when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, economic hardship led to widespread poaching. Saiga horns, valued at up to $150 per kilogram in traditional medicine markets, became more valuable than gold to struggling rural communities.

Expert Analysis

Conservation biologists consider the saiga recovery one of the most successful wildlife comebacks in history. The turnaround required coordinated efforts between the Kazakhstan government, international conservation groups, and local communities. Key strategies included hiring former poachers as park rangers, creating economic alternatives for rural communities, and using satellite tracking to monitor herds.

The 2015 mass die-off, which killed over 60% of the global population in just weeks, was caused by a normally harmless bacteria that turned deadly due to unusual weather conditions. This highlighted how climate change creates new risks for wildlife. Scientists now monitor saiga health more closely and have emergency response plans for disease outbreaks.

Additional Data and Fact Reinforcement

Recent population surveys show approximately 2.3 million saigas across Kazakhstan’s three main populations: Ural (western), Ustyurt (southwest), and Betpak-Dala (central). This represents a 4,500% increase from the 2005 low point. For comparison, the American bison recovery took over 100 years to achieve similar percentage growth.

The economic impact is significant. While conservation success generates eco-tourism revenue (approximately $2 million annually), farmers report crop losses exceeding $5 million per year. A single saiga herd of 10,000 animals can consume as much vegetation as 50,000 sheep, creating competition with livestock for grazing land.

Related News

Kazakhstan’s saiga success has inspired similar conservation efforts across Central Asia. Mongolia recently launched a program to protect its smaller saiga population, while Russia is strengthening anti-poaching efforts in Kalmykia. The United Nations recognized Kazakhstan’s saiga conservation program as a model for other countries facing wildlife crises.

In 2023, Kazakhstan hosted the first International Saiga Day, bringing together scientists, conservationists, and government officials from five countries. The meeting established new guidelines for managing growing populations while maintaining genetic diversity and migration corridors.

Summary

The saiga antelope’s journey from near extinction to abundance demonstrates both the power of dedicated conservation and the complexities of wildlife management success. While their recovery is celebrated globally, Kazakhstan now faces the challenge of balancing conservation with human needs. The government is considering controlled hunting permits, compensation programs for farmers, and wildlife corridors to reduce human-wildlife conflict. This “victim of its own success” scenario offers valuable lessons for conservation efforts worldwide.

Public Reaction

Rural communities have mixed feelings about the saiga boom. Farmers in western Kazakhstan have organized protests demanding government action on crop damage, while eco-tourism operators celebrate increased wildlife viewing opportunities. Social media shows divided opinions, with urban residents generally supporting conservation while rural inhabitants call for population control measures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What makes saiga antelopes so unusual looking?

A: Saigas have an inflated nose structure that looks like a trunk. This unique adaptation filters dust, warms cold air, and helps males make loud roaring sounds during mating season. They’re often called “living fossils” because they’ve remained unchanged for thousands of years.

Q: Why are saiga horns valuable?

A: In traditional Chinese medicine, saiga horn is believed to treat fevers and headaches. While there’s no scientific evidence for medical benefits, horns can sell for over $300 per kilogram on black markets, making poaching profitable despite being illegal.

Q: How did conservationists save the saiga?

A: Success came from combining strict law enforcement, community engagement, and science. Rangers patrol protected areas using drones and satellites. Former poachers were hired as guards. Scientists track herds with GPS collars. Local communities receive benefits from eco-tourism, creating economic incentives for protection.